“Juan: Singular Sensation”, New York’s First Immigrant

Jamie Lewis

Jamie H. Lewis is a graduate of the SUNY New Paltz Social Studies Master of Arts in Teaching (M.A.T.) program

“Juan Rodriguez, first merchant and non-Native American resident of Manhattan Island in 1613.” Watercolor by Charles Lilly, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

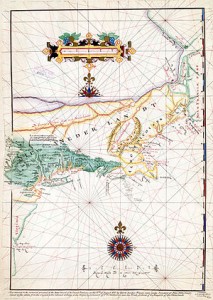

In 1609 the English explorer Henry Hudson discovered the river that now carries his name. Today we make a major hullaballoo around this alleged “first European contact”, but back then there was little interest – even from those who’d sent him. However, the rough map of the lower river Hudson provided his Dutch masters was passed along to other traders.

One company, the van Tweehuysen syndicate, was keen to get a foothold in the burgeoning fur trade; it sent out skipper Hendrick Christiaensen to investigate in 1611. Upon arrival, the wary captain anchored away from the unfamiliar coast, and made sorties ashore. During one of these he kidnapped two boys from a local Lenape village. Christiansen felt the two boys – he renamed them Orson and Valentine – would generate public interest upon his return to Amsterdam. This was the same sort of calculated publicity stunt that echoed Columbus and pre-dated John Rolfe’s promotional promenade of Pocahontas by five years.

Unfortunately for Christiaensen, the publicity meant his new highly profitable source of furs was now an open secret.

The next spring, a Dutch merchant working for the same company, Adriane Block, returned to map the area in order to establish a permanent trading post. Block and the van Tweehuysen company enjoyed two months of uninterrupted trade. Then when he was preparing for the return journey to Amsterdam in the late summer another Dutch ship, captained by Thijs Mossel, arrived in the Hudson Bay via Santo Domingo, the biggest port in Spanish Hispaniola – the island we now know as the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

Captain Mossel had a secret weapon aboard: Juan (or sometimes Joao or Jan) Rodriguez, a gifted linguist hired in Hispaniola to act as interpreter. Born in Santo Domingo to an African mother and a Portuguese sailor, Rodriguez neither looked, sounded nor thought like his employers. Whilst the merchants argued about prices and market shares, Rodriguez apparently decided that a return trip to the West Indies was not in his best interests (As the mulatto child of a slave, his future prospects in the West Indies or the Netherlands were equally poor). He obtained the balance of his salary from Mossel and promptly departed for the wooded shoreline of Mannahatta (from the Lenape word meaning “land of many hills”).[i]

Taking up residence on shore is what cements Rodriguez’ place in the history books. Previously, the Dutch had stuck to the security and relative comfort of their anchored vessels. Rodriguez decided to set up shop and trade the goods he’d received from Mossel to the local tribes. His plan obviously worked, because when Block, Mossel and Christiaensen returned, not only had Rodriguez survived the winter – he’d established a business relationship with the Lenape.

We have an incredibly detailed account of what happened next thanks to the work of Dr. Simon Hart, an archivist for the Lutheran church in Amsterdam. Hart translated mountains of notorial records containing dozens of first-hand testimonies from the crews and the merchants themselves, records that were later turned over to the New York Public Library. (Hart published his own history of the colony in 1959.)

Rodriguez approached Christiaensen and proposed a collaboration, to which the latter agreed. When Mossel did return, he was publicly furious that Rodriguez had double-crossed him. Towards the end of April 1613, when a canoe of Lenape paddled out to meet Christiaensen’s ship to trade, Mossel’s crew fired on the canoe and then rammed it with their boat, forcing the natives to seek refuge on Christiaensen’s sloop.

Mossel’s crew then turned their attention to Juan Rodriguez. Seeing them approachwith possibly murderous intent, Rodriguez fired a shot from his musket but was overwhelmed by four crew members, who took his musket and attempted to arrest him. Rodriguez grabbed a sword from one and fought his way back to the sloop and the protection of Christiaensen’s crew. Mossel’s crew withdrew in frustration whilst hurling a series of racist epithets, the more offensive of which the court records of 1614 refused to repeat.

That was the last record of Rodriguez that we have. He seems to have avoided the Dutch for the rest of his life. But regardless of his fate, in those few months Rodriguez not only became the first immigrant to move to New York, but also the first African, the first Latino, the first resident of European descent, the first Dominican, the first business owner and the first black man to be arrested in New York by white men. He anticipated, in a single persona, the diversity of New York.

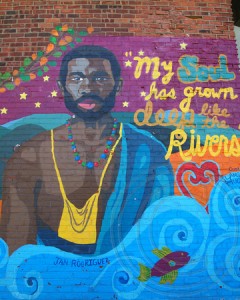

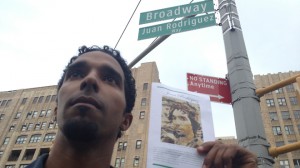

Rodriguez’ legacy is remembered with a plaque and mural in Riverside Park on the Upper West Side. In 2012 on the 400th anniversary of his move to Manhattan, the city co-named a 59-block-long stretch of Broadway starting in Washington Heights as Juan Rodriguez Way, an important tribute to the historic status and recognition of the substantial local Dominican community.

What of the rival merchants; the fledgling Dutch trade and the two kidnapped Lenape boys?

Christiaensen headed further up the Hudson and built a fort for protection during the winter, which he named Fort Nassau. Block returned to the area a couple of weeks later and threatened to sink Mossel. The two remaining factions were so busy arguing that they failed to notice a fire had mysteriously broken out on Block’s heavily-armed ship, which promptly sank. (This had more than a whiff of suspicion about it, but Block never accused Mossel directly.) Amazingly, the soggy remains of Block’s ship were discovered centuries later by workers excavating the foundations for the World Trade Center.

Several of Block’s crew mutinied and captured Mossel’s ship. Just as Mossel had claimed to have nothing to do with the fire that destroyed Block’s ship, Block expressed surprise and protested his innocence in the capture of Mossel’s ship. The mutineers set off for the West Indies in Mossel’s ship, leaving the Dutch merchants to face a winter in New York. The fact that they left him behind with Mossel seems to confirm Block’s version of events.

Mossel and Block were eventually picked up and returned to the Netherlands, where they promptly started mutual litigation. Block came off the worst, eventually being forced to pay for the loss of the 6 valuable cannon that sank with his ship. Whilst they were in court arguing, the Dutch government granted the exclusive trading rights to group of merchants who referred to themselves as The New Netherland Company. For the next 60 years, many Dutch colonists would follow in Rodriguez’ footsteps.

The harshest fate befell Christiaensen: he continued to travel and trade with the two kidnapped Lenape boys, Orson and Valentine, using them either as translators or a warning to others. In 1616, on a return trip to Fort Nassau, Orson finally got his revenge and murdered his publicity-hungry Dutch captor.

[1] Mossel paid him “eighty hatchets, some knives, a musket, and a sword” which seems unusually generous. As Hart notes, “Later it appeared that this payment also included an advance on services still to be rendered” which begs the question: Was Rodriguez still working for Mossel? Mossel’s behaviour upon his return (outrage and the arrest attempt when he discovered Rodriguez was working for Christiaensen) would seem to confirm this.

Jamie H. Lewis was raised in a museum. He teaches, writes for various historic publications including the Museums Journal and The 28th. He knows he needs to get out more.

Sources:

Hart, Simon. “The Prehistory of the New Netherland Company.” Amsterdam, City of Amsterdam Press, 1959.

Phelps-Stokes, I. N. “The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909” New York, 1928, Vol. VI, 4.6